'This has the potential to replace all fossil energy sources'

Richard Hogenkamp

05/05/2023

Hydrogen is seen by some as the fuel of the future. The problem is that it is made artificially and uses other

— often fossil — energy sources. But what if you could just produce it out of the ground?

Hydrogen is clean energy because only water vapor is released during combustion. Illustration: Sjoerd van Leeuwen

Colorless, tasteless, odorless, invisible. And untraceable, at least until recently. Hydrogen, a clean source of energy, could be found in large quantities in the earth’s subsurface. A large reservoir was recently discovered in Spain, at the foot of the Pyrenees. It is the first natural hydrogen reservoir in Europe that has been proven. Experts call it promising.

‘To be honest, I have always assumed that this couldn’t exist, hydrogen that is hidden in the earth’s subsurface and that you can pump out,’ says Richard van de Sanden, professor at Eindhoven University of Technology. ‘Hydrogen consists of very small molecules that can pass through almost anything. So the idea is that hydrogen that is produced somewhere in the earth simply escapes because it finds its way up, passes through the earth’s crust and evaporates into the air.’

Van de Sanden is in favor of the production of hydrogen in electrolysers as a new, additional energy source, in addition to oil, gas and energy from the sun and wind. But he is also someone who warns that hydrogen should not be seen as a panacea, because it has to be man-made and we are not very efficient at it yet. The production is expensive, dirty or both. The fact that hydrogen may now be present in large quantities in the earth itself makes him optimistic. “This looks really positive, yes.”

Logical thinking

Ian Munro, CEO of Helios Aragón, understands that the discovery of natural hydrogen in the subsurface appears to defy science. He wouldn’t have thought of looking for it a year and a half ago. It is his Anglo-Spanish company that recently discovered the underground hydrogen reservoir in the northern Spanish region of Aragón. The reservoir is located near the village of Monzón, about 50 kilometers from the French-Spanish border, at the foot of the Pyrenees. “Based on what we know now, I think we can provide all industry in the wider Monzón area with energy from this hydrogen reservoir.”

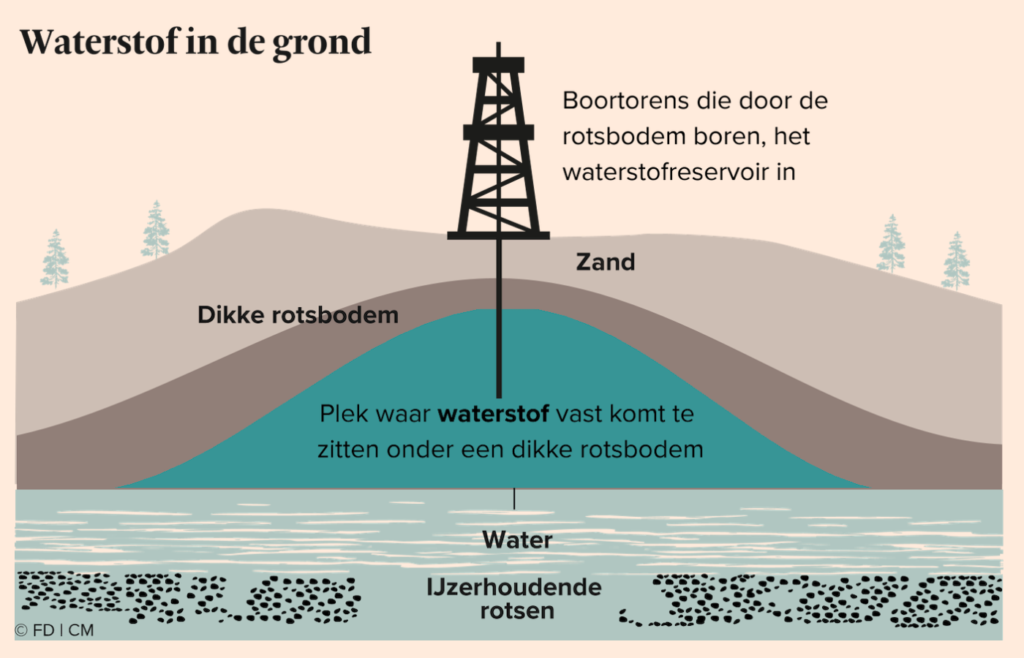

“When we started thinking logically, the Aragón region seemed like a place where hydrogen could be located,” says Munro. ‘What you need is a source in which iron-rich rocks and water come together. Then hydrogen is formed. What you also need is a subsurface structure that prevents the hydrogen from escaping.’ Munro’s company tried at Monzón and it was a hit, at 3.5 kilometers depth. Hydrogen is trapped there under a thick layer of salt. Helios Aragón wants to drill through that layer of rock and produce the hydrogen. And that can be done cheaply, Munro believes. ‘Our estimate is that we can produce it for €0.75 per kilo. That is at least half the cost of making grey hydrogen, currently the cheapest form of hydrogen, but grey hydrogen is polluting. Natural hydrogen is a completely clean source of energy.”

Urban legend

Munro became enthralled with natural hydrogen after delving into the accidental discovery of a reservoir in Mali. “I thought it was very interesting what happened there. But you don’t necessarily want to be in Mali as a company given the instability. It is not for nothing that many years after the discovery there is still no commercial exploitation of the Malian hydrogen reservoir.’

The story of the Malian find almost sounds like an urban legend, but it has been recorded. In 1987, drilling for water was done near the village of Bourakébougou. Wind came up from the hole created by the drilling. No one understood what it was and where it came from. When one of the men drilling for water lit a cigarette at the hole, it exploded in his face. He sustained burns. A fire started above the hole in the ground that would not stop. It took weeks to put out the fire. When they finally succeeded, frightened villagers closed the hole.

It took 25 years for the remarkable event in Bourakébougou to be revisited. In 2012, the Canadian Chapman Petroleum investigated the village. In a mobile laboratory in the sweltering desert, researchers discovered that what came up from the hole was 98% pure hydrogen.

2012 was also the year in which the Malian civil war began, seriously worsening conditions for hydrogen extraction. An installation was still connected to the hydrogen source, but it is only for local use. The 4,000 inhabitants of Bourakébougou have had electricity ever since and use it for refrigerators and lighting their homes, luxuries unknown to residents of many other villages in the desert of Mali.

Inexhaustible

The hole in the ground has been supplying the villagers with electricity for more than ten years now. The source of hydrogen in Bourakébougou seems inexhaustible. And that makes sense, say people who have studied it. ‘Hydrogen is produced continuously in our earth. In that respect, it cannot be compared to oil or gas, which only arise after millions of years of favorable conditions and run out when you extract it,” explains Viacheslav Zgonnik. Zgonnik is CEO of Natural Hydrogen Energy, a company that drills for natural hydrogen in the US state of Nebraska.

He does that just like Helios Aragón at a depth of 3.5 kilometers. The source where Natural Hydrogen Energy is at work is near Geneva, close to the first step of the Rocky Mountains. Zgonnik is a few steps further than his colleagues in Spain. ‘Because the great thing about the United States is that you don’t have to wait as long before you can exploit an energy source.’

Zgonnik says he has an “obsessive fascination” with natural hydrogen. “I first heard about it in 2014, hardly anyone else talked about it. I started thinking and thought that it would make perfect sense for there to be large hydrogen reservoirs in the subsurface.”

Permits, not subsidies

When he talks about the benefits of natural hydrogen, he becomes even more enthusiastic. ‘It’s cheap. You can take it to where you want to use it through the existing infrastructure of gas pipelines. And the supply never runs out, because as long as iron-rich rocks and water remain in contact with each other deep in the earth, new hydrogen is constantly being made.’

When asked about the yield of the hydrogen source in Nebraska, Zgonniks remains silent. “At this early stage, this is still company-sensitive information that I cannot share. But based on what I know now, I can say this: I believe that natural hydrogen has the potential to replace all fossil fuels. Yes, I know that’s quite a statement, but I’m convinced.’

Ian Munro in Aragón is a little more cautious, but he is also optimistic. The potential is very great. There is a big “but”: we must be able to extract and transport the hydrogen. In Europe we need permits for that. That’s what we’re working on right now. Every time I talk to government representatives about it, they are amazed. I am not asking for subsidies, as producers of clean but expensive green hydrogen do. I have investors and we can produce cheaply, four to five times cheaper than green hydrogen. I don’t need a subsidy. All I want is legislation. Once we have that, I will know more about exactly what we are producing and how important natural hydrogen will be in the energy mix.’

Burning zeppelin

Are there only positive messages about natural hydrogen? Richard van de Sanden of Eindhoven University of Technology points out the risks. “This all sounds promising, but if we are going to pump, store, transport and use hydrogen, we need to think about how we keep it safe. Hydrogen is simply not as safe as other energy sources that we already know, such as fossil fuels, sun and wind.’

Viacheslav Zgonnik: ‘The first image that comes to mind when I talk about hydrogen is a burning zeppelin.’ That is not surprising: the images of the burning Hindenburg Zeppelin from 1937 are iconic. Thirty-five people died in the blaze. The impact of that 85-year-old image is still felt by pioneers in the hydrogen world. Zgonnik: ‘That is not entirely fair. We have already learned a lot about the risks of hydrogen. In the beginning we also knew little about how safe or unsafe oil and gas were. Only by starting can we get to know all the properties of hydrogen and find ways to handle it more safely.’

Not in the Netherlands

Munro and Helios Aragón think they have built in sufficient safety guarantees to obtain the necessary approvals. Then they could start hydrogen extraction in the north of Spain next year. Meanwhile, Munro is also looking to other places in Europe before, as he puts it, “the big boys turn to natural hydrogen.” Munro is talking about the major energy companies of the world.

The search takes place in areas that have similar subsurface properties to those in Mali and Aragón. “Then you usually end up near mountain ranges. We are now doing exploratory work in Germany, Poland and Hungary. I think Sweden also has good potential.’

When asked about the chances for the Netherlands, a knowing smile appears on Munro’s face. ‘I have been surprised a number of times in the past year and a half when it comes to natural hydrogen, so I don’t dare say anything with certainty. But based on what we know now, I wouldn’t look in the Netherlands.’

A color palette of hydrogen

Hydrogen is clean energy. Cars and buses can drive on it, and it is already being used on a small scale in industry. When hydrogen burns, only water vapor is released. Hydrogen is colorless. Yet science uses color codes to distinguish different types.

Brown hydrogen is the most polluting type there is. Coal or lignite is burned to make this hydrogen and many harmful substances are released, in addition to CO2, for example, also sulfur dioxide.

Grey hydrogen, the most common form so far. Oil is used for production, or natural gas that is pressurized and heated. This releases significant CO2.

Blue hydrogen is produced in the same way as grey hydrogen, but the difference is that the CO2 released during the production process is captured and stored underground, for example in depleted natural gas fields.

Purple hydrogen is produced using nuclear energy. The advantage is that no CO2 is released, but there is nuclear waste.

Green hydrogen is made with renewable electricity. Electricity generated by solar panels and wind turbines is converted into hydrogen in an electrolyser, a method of storing solar and wind energy for later use.

Orange hydrogen is hydrogen produced by pumping water into iron-rich underground rock formations. The reaction between water and the iron-rich rocks releases hydrogen, which is then pumped back up.

White, gold or natural hydrogen is made by the earth itself in places where, underground, water and iron-rich rock formations come together. If successful, this hydrogen will be the cleanest and lowest cost of all types of hydrogen.

Read the full article:https://fd.nl/bedrijfsleven/1475103/dit-heeft-de-potentie-om-alle-fossiele-energiebronnen-te-vervangen?